Eight years ago, Michael Tillem grew tired of watching people die from the disease of addiction. With 14 years of sustained recovery under his belt, Tillem “felt called to live in the solution.” So, he dedicated his life to helping those who still suffer, working tirelessly in “relentless pursuit of the greater good.”

At least, that’s one version of the story.

Tillem and his wife, Kimberly Braine-Tillem, are known as the founders and leaders of Journey House Foundation – a tax-exempt nonprofit serving people in early recovery.

But beneath the display of charity, the Tillems have been building a business empire – one that sometimes benefits them at the expense of those they serve.

This installment explores the Tillems’ rise to prominence, their growing recovery enterprise, questionable and potentially illegal business practices, and – most importantly – the gap between what they advertise and what former participants say they provide to people in that vulnerable, life-or-death stage of early recovery.

>Dropdown page navigation menu<

- The business of recovery: a fast track to success

- ‘We can help you’

- The Medicaid cash cow at Journey House

- ‘The guys at the top are greedy’

- When clients are ‘staff’

- A whole house fell through the cracks

- Medication ‘monitoring’

- Playing doctor

- Urine drug testing: false claims

- Silence all the way to the top

- A note on solutions

The Business of Recovery: A Fast Track to Success

Before the Tillems married in 2007, Michael Tillem “didn’t have a dime.”

By all visible accounts, the new couple worked hard and lived a modest life. Tillem started a landscaping business and worked various sales jobs, while Braine-Tillem worked for a local Christian radio station and then for Mt. Vernon Baptist Church.

After a seven-month stint as a local deli entrepreneur in 2014, Tillem “lost everything in the restaurant business,” he wrote in a public Facebook post. “We downsized our home, we cut back to bare essentials …”

After getting some experience working at The McShin Foundation – a local recovery community organization that runs recovery homes – Tillem launched his own venture in recovery housing. In April 2016, he founded Journey House Richmond, LLC, starting with a couple of houses in Henrico County’s Lakeside area.

By the following year, he had joined the Virginia Association of Recovery Residences (VARR), which had a small group of members and different leadership than it has today.

In March 2017, VARR suspended Tillem’s membership for ethical violations.

From the board meeting minutes:

According to two sources familiar with the incident, Tillem bought himself at least one expensive suit from Francos and was caught charging the purchase to a wealthy Journey House resident, who didn’t manage his own finances. Tillem disguised the purchase as “court clothes” for the resident, one source recalled.

A few months later, Tillem and his wife started Journey House Foundation. In the name of ministry, they rallied a strong base of supporters – churches, businesses, nonprofits and individuals – all willing to donate time and resources to support the nonprofit’s mission.

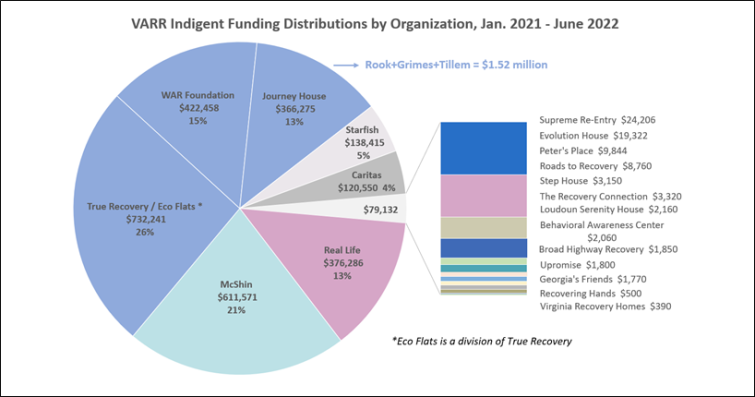

Despite marrying their public image to a charitable cause, the Tillems are in the business of recovery, and always have been. Since its inception, the nonprofit face of Journey House has been inextricably linked with the for-profit Journey House Richmond and entangled with a growing conglomerate of LLCs – some owned wholly by Tillem, others owned jointly by him and his associates in the VARR coterie.

By August 2018 – just 18 months after Tillem’s membership suspension – VARR welcomed him back into the fold. 1

The following year, Tillem co-founded River City Residential Services (RCRS) – a small clinically-managed low-intensity residential treatment company – with David Rook, Jimmy Christmas and Dr. Peter Breslin, all of whom were involved with VARR at the time.2

Journey House Foundation supplied participants to RCRS, shuffling them back and forth as relapses occurred or reoccurred.

Meanwhile, participants of Journey House Foundation were supplying cheap labor for Tillem’s Property Maintenance & Landscaping, LLC (TPML), according to several former residents and employees. At the same time, Journey House Richmond, LLC, was collecting bed fees from Journey House Foundation, residents and families. The LLC grew from operating 50 to 82 beds in two years. 3

In 2019, the Tillems opened a Journey House Foundation recovery center in a “joint venture” with Mt. Regis Treatment Center – an inpatient treatment facility in Salem to which Journey House referred participants.

That same year, Tillem was chosen as one of 15 Allen & Allen Hometown Heroes, people who were honored for their “untiring commitment to helping others.”

“(He) is always giving back to our community, never expecting anything in return,” Kimberly Braine-Tillem told the publisher.

By December 2020, the Tillems owned at least two private homes – one in Glen Allen ($433,000) and another in Montpelier ($265,000). By mid-2021, Tillem also owned four of the nine Journey House recovery residences for which the Tillems solicit furniture donations and fill with participants of Journey House Foundation.

Starting in November 2021, Journey House Richmond, LLC began receiving payments from VARR for program services – the same program services made possible by Journey House Foundation’s staff, volunteers and resources.

In December 2021, just seven years after Tillem “lost everything in the restaurant business” and four years after his last court judgment for unpaid debt4 – he was already thinking about early retirement, he wrote in a public Facebook post.5

***

As is the case with VARR, Journey House Foundation is largely controlled by the same people who stand to benefit from its resources.

The Tillems – both full-time managerial employees of Journey House Foundation with interconnected business interests – have always held three out of four executive positions on the board of directors: Tillem as board president and Braine-Tillem as both treasurer and secretary.

From 2017 to 2021, the position of vice president was held by Reginald Nash, who financed three of Tillem’s recovery house properties – homes that are sustained in part by the foundation’s resources. In 2022, Nash was replaced by Woodrow Vickery – a longtime personal friend of Tillem’s who has since assumed the role of board chairman. (I was unable to locate Nash or Vickery for comment.)

Unlike many nonprofits, the Journey House Foundation website contains no information about its governing board.

***

By the end of 2022, preparing to launch a for-profit behavioral health company in partnership with Jimmy Christmas, the Tillems relocated the Journey House Foundation center to a more spacious office park on Shrader Road.

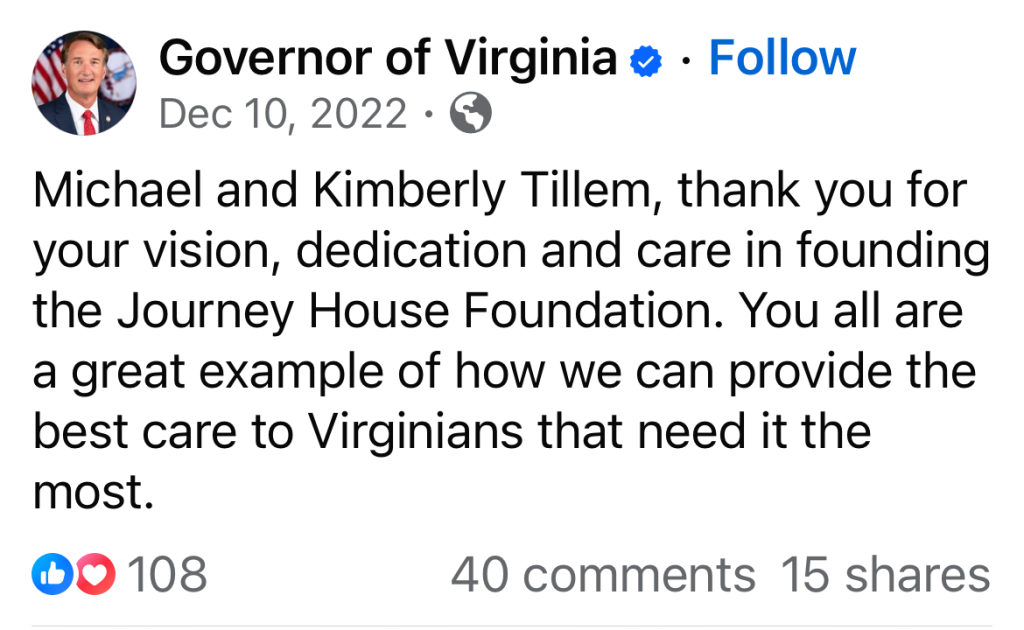

Republican Gov. Glenn Youngkin and his wife appeared as honored guests at the ribbon-cutting ceremony.

Between 2023 and early 2024, Tillem opened two new recovery step-up homes, obtained licensure for two Journey House behavioral health companies (one of which closed) and acquired a 1910 farmhouse that he plans to use as a Journey House “therapeutic farm,” according to private Facebook posts shared by a confidential source.

In partnership with Journey House Foundation – the consistent face of the business enterprise – the Tillems’ ever-expanding collection of for-profit ventures produce more and more money for them.

But what about all the people in that vulnerable phase of early recovery who cycle through their doors? What are they getting?

According to many former residents and employees, it’s a far cry from “the best care” that Youngkin described. And it’s a lot less than what the Tillems advertise.

>Dropdown page navigation menu<

- The business of recovery: a fast track to success

- ‘We can help you’

- The Medicaid cash cow at Journey House

- ‘The guys at the top are greedy’

- When clients are ‘staff’

- A whole house fell through the cracks

- Medication ‘monitoring’

- Playing doctor

- Urine drug testing: false claims

- Silence all the way to the top

- A note on solutions

‘We Can Help You’

Michael Tillem is a “phenomenal” salesman, said former resident and employee Courtney Hammond. He’s not “the worst guy,” she said, but “he is a master class in bullshit and, like, selling you on any pipe dream ever.”

“People don’t know what they’re getting into when they go (to Journey House),” said a former long-term resident and volunteer who will be called Leah. “Mike just sells the program way too well.”

Leah listened as Tillem promised residents and their families everything from getting their driver’s licenses, to getting cars, to getting their kids back. “We can help you,” she heard him say to them.

“One of his little tricks,” she said, was to put it in writing on a white board, making it seem as if it was really going to happen.

After the string of promises, he would tell them “hang tight” and “do what we say” – a sentiment that was also reflected in the Journey House welcome letter to new residents:

“What’s best for you” often turned out to be what was best for the Tillems’ business.

“Trusting the process” sometimes meant living in unsafe environments “staffed” by newly clean or sober residents, providing free labor, getting medications “prescribed” by nonmedical staff, providing a constant supply of urine for questionable drug testing operations, and participating in low-quality outpatient treatment programs with Tillem’s business partners – instead of getting mental health services tailored to their needs.

Amid all the reported dysfunction and exploitation, there were undoubtedly genuine and supportive relationships formed between residents and staff. (We’ll get to those too.)

But dozens of former residents echoed what this one said:

“It felt wrong the whole time. … I want to believe, I mean, I think Mike Tillem and everybody, they’re trying to help people, but it just seemed like a lot of it was manipulative. … I definitely get the vibe they get as much out of you as they can and then just kind of send you on your way.”

>Dropdown page navigation menu<

- The business of recovery: a fast track to success

- ‘We can help you’

- The Medicaid cash cow at Journey House

- ‘The guys at the top are greedy’

- When clients are ‘staff’

- A whole house fell through the cracks

- Medication ‘monitoring’

- Playing doctor

- Urine drug testing: false claims

- Silence all the way to the top

- A note on solutions

The Medicaid cash cow at Journey House

“As soon as you walk in the door, they give you Medicaid…they send it over to River City,” said Brian Kelly, who lived at Journey House in 2022.

As is the case with other VARR-certified operators I’ve covered, Tillem has a heavy hand in his residents’ outside mental health care.

Anyone who came to Journey House with private insurance was instructed to switch to Medicaid, according to former residents and employees.

Journey House then steered them into the Medicaid-funded Intensive Outpatient Program (IOP) at River City Comprehensive Counseling Services, owned by VARR Vice Chairman Jimmy Christmas – the same program that was packed with participants from True Recovery, WAR Foundation and Starfish Recovery & Wellness; the same one many residents attended online, where they say “real therapy” wasn’t taking place; the one that allegedly paid kickbacks to recovery house operators (VARR leaders) who forced their residents to attend the IOP under the threat of eviction or jail (see parts 1 and 4).

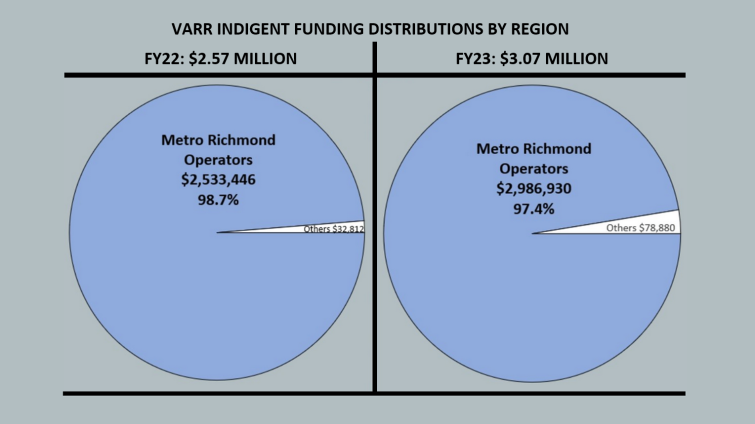

Tillem hasn’t served on the VARR board anytime in recent history, but he’s been part of the Richmond-area inner circle of highest-funded operators – and part of River City’s ever-expanding Medicaid empire that has been fueled largely by forced treatment imposed on recovery house residents.

Brian Kelly went to Journey House in 2022 after he spent 49 days at an inpatient treatment center. He was ready to be done with intensive treatment and start focusing on work. But Journey House had different plans for him.

“I was really pressured (to do IOP),” he told me. “If you didn’t do it, you were going to be targeted for removal. I promise you that.” Just as many others reported: “They’re shown one way: River City. And it’s really shoved down their throats.”

After I sent the Tillems a list of questions for this article in May, new language appeared on the Journey House website: “We allow our participants freedom of choice when finding counseling and therapy services.”

Kelly didn’t want to lose his home, so he begrudgingly completed 12 weeks of River City’s virtual IOP. There were about 15-20 people in each session, he said. “It was so silly…I just login, say hi, do my feelings check real quick and then cut my screen off and then go to the gym, workout. The whole three hours I’ll be at Gold’s Gym. I’ll be listening to music, cut my mic. … (I could) go to the store, go out to dinner. It didn’t matter.”

Residents who went to the Journey House center during the day often attended IOP on their phones amid everyone else at the center. They walked around with phones in their pockets, sometimes on speaker for anyone within earshot to hear. They would be “sleeping, reading books, eating, doing everything but (IOP),” one former resident said. “All they had to do was be logged onto their phone.”

Journey House “a hundred percent forced (residents) into IOP,” said Rob Adams, a former specimen collector for Diax and Ethos Laboratories who was based at the Journey House center. “(Tillem) said (to them), ‘You want to stay out of jail right? You don’t want to go back to probation do you? Then you need to do your IOPs.'”

Participants who missed IOP were punished with earlier curfews, overnight restrictions or losing access to their own vehicles, he said. “One was supposed to go to the food bank, and he didn’t do his IOP. So they purposely left without him so he couldn’t go to the food bank.”

IOP is “all River City,” said Leah – the pseudonym for the former long-term resident and volunteer, who also conducted intakes for Journey House.

It’s a huge waste of time that comes with bigger issues. If the person has a job and can’t make their job work around IOP, staff doesn’t give two shits and just tell you to figure it out.

As I presented in Part 1, policy established by the National Alliance of Recovery Residences (NARR) – VARR’s parent organization that sets the standard for ethical recovery homes – is clear when it comes to forcing clinical services with outside providers: It’s not permitted.

- “Residents must always be empowered to choose or reject the external services and/or providers suggested by the residence’s owners/operators.”

- “A resident’s right to accept or reject recommended services…is an essential component of the Social Model of Recovery” – the model all recovery homes certified to NARR standards are based upon.

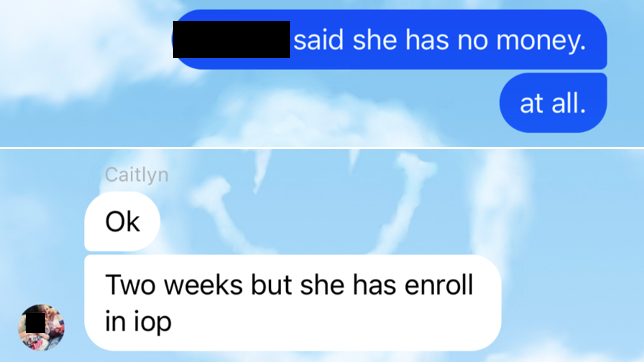

In 2022, a participant I will call Brett had recently completed an intensive program with a local recovery organization and was looking for a transitional sober living home. He went to the Journey House center with his mom, sat down with Tillem and explained what he needed: a safe place to live where he could focus on working and attending 12-step meetings, and where he would be held accountable for his sobriety – everything typical of a sober-living environment.

When Tillem broached the subject of IOP, Brett said he made it clear he was not interested. And before his mom handed over a check for Brett’s first month at Journey House, Tillem promised Brett he wouldn’t force him into IOP.

Within about two weeks of moving into the recovery house, Brett found a job and started working. “That’s when I realized they go back on their word,” he said.

First, staff told Brett he had to at least complete an assessment with River City. He obliged but said he repeatedly told the clinician he was not interested in IOP and did not have time for it. The next day or soon after, Journey House staff informed Brett that he qualified for IOP (as in, Medicaid would pay for it). And because he qualified, he would be required to attend.

Brett quickly discovered there was no point in arguing his case, he said. “I was specifically told by Mike Tillem, either I do IOP at River City or I would be kicked out of Journey House.”

River City’s IOP offered two different time slots, both of which overlapped with Brett’s work schedule. He said he would have to miss half of every IOP session no matter which time slot he chose. “All you need to do is just log onto Zoom so they see that you’re there,” Tillem told him. “He said blatantly to me, ‘I get paid from the IOP referrals. That’s how I keep the lights on and am able to scholarship people like you.'”

“In some industries, it is acceptable to reward those who refer business to you. However, in the Federal health care programs, paying for referrals is a crime.”

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General

Kickbacks in healthcare can lead to corruption in medical decision making, patient steering (to specific providers), unfair competition, increased program costs and overutilization of federal funds (OIG). In short, kickbacks put profits ahead of patient care.

According to another former resident, Tillem said IOP was a requirement for providing financial assistance to residents. “He would straight up tell the guys, ‘I need you to do 90 days of IOP if you want to get the funding for your rent.'”

According to a third resident who left Journey House in late 2023, employees told her they required IOP “so that they can draw grants.”

When Journey House relocated to the new center on Shrader Road in late 2022, participants attended IOP together in a designated group room, while the facilitator joined virtually.

According to former resident MJ, these groups weren’t interactive or engaging. And with upwards of 10 people in a single group, from what she recalled, it was easy to skip the group without anyone noticing.

Adams said the same thing – “It’s all the time that people are not staying in those IOPs.”

Sometimes people in early recovery don’t want to do hard things, Brett said. But forcing IOP wasn’t about pushing people to do difficult things for their own good. It just seemed like it was all about making money, he said. “You can get the same information that they’re preaching at IOP…from anybody in recovery for free.”

Jimmy Christmas did not respond to a request for comment.

In late 2022, Tillem partnered with Christmas to launch Journey House Behavioral Health, LLC. According to the application on file with DBHDS, Tillem and Christmas had 50/50 ownership of the business.

In 2023, DBHDS issued a license for the LLC to provide substance abuse IOP at the Journey House Foundation Center. The application showed they projected initial annual revenue of $540,000 for the IOP – a program that would inevitably be filled with Journey House residents.

The IOP partnership closed in October for unknown reasons. The following month, Tillem founded Journey House Behavioral Health RVA, LLC, which he solely owned. By January 2024, he was licensed to provide a substance abuse Partial Hospitalization Program (PHP) at the Journey House Foundation center. The application did not include projected revenue, but Medicaid reimburses for PHP at double the rate it does for IOP.

I am in the process of researching several new IOP/PHP business partnerships between Jimmy Christmas and recovery house operators. If you have experience with an IOP or PHP affiliated with a recovery house, please contact me.

>Dropdown page navigation menu<

- The business of recovery: a fast track to success

- ‘We can help you’

- The Medicaid cash cow at Journey House

- ‘The guys at the top are greedy’

- When clients are ‘staff’

- A whole house fell through the cracks

- Medication ‘monitoring’

- Playing doctor

- Urine drug testing: false claims

- Silence all the way to the top

- A note on solutions

‘The guys at the top are greedy’

Along with participating in forced group therapy sessions, a day in the Journey House program consists of peer-to-peer groups and activities led by volunteers and staff of Journey House Foundation.

The day program came with mixed reviews but some common themes.

Unorganized, chaotic, a waste of time – such were the frequent descriptions provided by former residents. But most of them also found positive things to say about certain components of the program. Some told me they enjoyed going to the gym a couple of days a week. Others said they liked the regular arts and crafts activity that was led by a community volunteer.

Several of the participants I spoke with pointed to at least one Journey House Foundation employee they connected with or admired:

“His heart’s in the right place” – former male resident (2022) describing former employee Rob S.

She was “very open, welcoming, easy to talk to,” said former resident MJ (2023) about former employee Richelle. “There’s a lot of amazing people there.”

Teri Anderson, who said she wouldn’t send her worst enemy to Journey House based on her overall experience, told me the former program director, Stephanie, was “really good.” Braine-Tillem was “so nice,” she said, and always remembered her name despite their infrequent interactions.

Aside from subjects, I interviewed 42 people for this installment – mostly former residents and employees, but also a few family members of residents and community members familiar with Journey House or the Tillems.

Perspectives on Michael Tillem’s intentions varied slightly.

One former employee called Tillem a “decent guy” and a “great leader.” In March 2023, a then-employee emailed me stating, “I know there are some real bad players in this field and I just (can’t) believe that Michael Tillem is one of them.”

But most said Tillem’s first priority is making money. The people in that life-or-death phase of early recovery often come second.

“Everything, everything about Journey House revolves around money. Mike Tillem sees dollar signs.” – former female resident (2020-2022)

“Mike Tillem sees you as a dollar sign.” – former female resident (2023)

“It definitely seems like it’s all about making money. … The people that are working there, they’ve got the right intentions. … (But) the guys at the top are greedy.” – former male resident (2022)

“He’s a great guy, but he really is focused on his money. I would say sometimes he gets his priorities kind of out of order.” – former male resident (2024)

“If they were getting money from someone’s family and they knew they were going to continue to get a ton of money from them, then they let people get away with crazy things that other people would have been kicked out (for) in a second. … I think that that was always very apparent there.” – former female resident (2020-2022)

“They just let that child do whatever the hell she wants,” Rob Adams said about a 17-year old resident at Journey House. “When (she) was forced to follow the rules she would run away. … When she came back the staff said she doesn’t have to follow the rules. She can do whatever. And that’s not what is supposed to be happening, but Mike wants the money the state pays him to have her there.” (Between July 2022 and December 2023, the state paid Journey House Foundation $357,700 to care for minors. The Office of Children’s Services declined to provide the number of children those payments represented, but former residents only informed me of two minors that lived at Journey House during that time.) “This kid’s over here just getting away with murder,” a former male resident said about the other minor at Journey House. “But because they’re cashing the check off of him, they let him do it.”

Like many recovery entrepreneurs, Tillem promotes his personal experience overcoming addiction as a marker of his ability to help others. In his words:

“Mike Tillem doesn’t use, but he’s not clean,” said Brittany Rich, a former resident and employee (2019-2020). “He gets off on getting over on people. It’s just a different addiction now. And it’s full blown.”

“Mike Tillem. Wow. I’ve been in recovery now for (many) years, and I have never seen anybody who has used recovery to enrich himself in the manner in which he does.” – recovery community member

Before quoting a price for the Journey House program, Tillem researched prospective residents on Facebook “to see how much money he could try to fleece out of mom and dad,” said Logan Adams, a former resident who also worked for Tillem (2020). “He has a smirk on his face when he says (he runs a nonprofit) because it’s a joke.”

“If he thought he could extract $4,000 or $5,000 or whatever the fee was…then he would pursue it until it was clear he couldn’t,” said a former male resident, who listened to Tillem’s “sales pitch” multiple times in early-mid 2019 (before Journey House had a recovery center to accommodate a program). “And he’s talking to moms and dads and comparing that $5,000 figure to maybe $25,000 that an actual treatment place would charge. So he’s saying, ‘Look, this is peer-to-peer recovery. It costs you this. This is what I’m going to do. This is where the kid’s going to live.’ Objectively, none of that’s a lie. I guess where it’s a little weird, these people are desperate. They don’t know what their kid or loved one really needs. And they have a guy saying, ‘You can trust me. Give me money and I’ll take care of them.'”

He added:

Tillem “announc(ed) to the world and to himself and everyone around him that he is out doing God’s work. And that’s not verbatim, but you know, that this is a nonprofit, he’s trying to help addicts and dah, dah, dah, he doesn’t collect money, dah, dah, dah. (It) was just a total farce. I mean, it was obvious this is a booming business. He’s growing his empire. … I thought (back) then that I was pretty sure he had very questionable morals, motivations, incentives, right? That he was always a different person to a different person, whoever he needed to be. He was still very much a sick addict. … And I just remember thinking that at the time, like, God, this guy is so sick. … But my negative opinion aside, you know, he seemed respectful enough to women, respectful enough to minorities…”

Were you offered a credit card instead of grant funds to pay for your first month at a recovery house? If so, please contact me.

In mid-late 2019, Sarah Rogoskey called Journey House looking for help after a week and a half of drug use on the streets. “I was really in bad shape,” she said. A staff member told her she could move into one of the recovery homes for $900, and two family members agreed to pay the fee. But when Rogoskey showed up at the Journey House Foundation center that day, the parameters changed. Tillem told Rogoskey she had to first attend an in-patient program at Mt. Regis Treatment Center – a Journey House sponsor. Upon returning to Journey House, she would then have to pay him extra fees for a “sober buddy” to stay with her. “Mike Tillem was like, ‘I want you to call your (family). I’m going to call your (family).’ And he did call my (family) in front of me, even after I told him (they) do not have any more money,” she said.

The thing that just got me was just that I was in desperate need of help. And they were just putting up every roadblock to be like, ‘Well, do this and we’ll help you. Do this impossible thing and we’ll help you.’ … It was as if I was watching a con man at work, thinking to myself, this is what he does all day long, is con desperate families into giving him more money based on first impressions of assumed wealth. … It didn’t feel like it was about helping addicts to me. It never felt that way to me.

Here’s the family member Tillem called that day:

He kept saying how bad Sarah was and how we were right to seek help and how she was not doing well. And I don’t know that he used the word ‘die,’ but it sort of was out there, like you know, ‘Anything can happen and you do have to get your daughter help. And this is what I think she needs.’ He also said, I think, that she needed to go to a rehab that he would send her to, and of course that would be more money, and that when she came back he needed more money for whatever sober living she was going to live in plus this daily partner. … I remember feeling very desperate and wanting help for her but also feeling like…this doesn’t seem like it’s going to work. And it seems like it’s more and more money that we don’t have.

When Tillem was unable to siphon more money out of her family, he turned Rogoskey away. With nowhere to go, she went back to using on the streets until she eventually found help with another organization.

“Of course that’s the fear,” the family member said. “That’s exactly the fear that your loved one is going (to go) back out. And we know the dangers associated with that. So there’s a great deal of fear in these decision makings. If I don’t do this, if I don’t find this money, what will happen? Will this be the time that they go out and we get that phone call?”

(Tillem – just like anyone working in the addiction recovery industry – is intimately familiar with the desperation and fear that family members experience in those moments they are faced with big financial decisions.)

“Find something that Mike Tillem does benevolently,” said David Rook, former VARR president and Tillem’s then-business partner, in a November 2022 interview. “Find something that he does that’s not self-serving. Anything. Find it and show it to me.”

>Dropdown page navigation menu<

- The business of recovery: a fast track to success

- ‘We can help you’

- The Medicaid cash cow at Journey House

- ‘The guys at the top are greedy’

- When clients are ‘staff’

- A whole house fell through the cracks

- Medication ‘monitoring’

- Playing doctor

- Urine drug testing: false claims

- Silence all the way to the top

- A note on solutions

When clients are ‘staff’

A large percentage of the Tillems’ workforce has always been made up of Journey House residents. This is common in peer-run organizations, but some, like Journey House, often promote residents to “staff” positions when they are barely sober.

Shortly after Brittany Rich first arrived at Journey House in December 2019, she attended an outside holiday party with other Journey House residents. The employee assigned to supervise Rich and her peers was newly sober himself, she told me. He came to Journey House as a participant not long before she did.

At the party, Rich relapsed on alcohol and alprazolam – a potentially lethal combination of substances. She was OK, but she passed out from intoxication before getting home that night. The next day, she said staff revealed they knew she was using at the party before they took the residents home. The employee supervising them even contemplated calling an ambulance. But instead, he did nothing. Rich was given minor sanctions the following day.

By reviewing social media posts and an old Journey House newsletter, I confirmed the supervising employee became the organization’s “care coordinator” just a few weeks after he arrived at Journey House as a newly sober participant.

“We hire from within,” Braine-Tillem said in a September 2023 interview with River City Podcast. “(We) always are looking for individuals who are thriving in their recovery and have a heart and a passion to give back.”

The Tillems promote from within, Rich said, because they can get free labor – that is, “until you feel like you have some worth again. And then you’re like, OK, you need to pay me.”

Within months of her moving into Journey House as a newly sober resident, Tillem offered Rich the position of intake coordinator. She worked Monday through Friday, roughly seven hours a day. At first, her only compensation for this full-time job was free rent. Then, she took on the role of house manager simultaneously, which was a “never ending” job. Eventually, she says Tillem started paying her a couple hundred dollars per week total, for both jobs. “It’s unfortunate,” she said, “because I know I’m not the only person that has happened to.”

About a year into her time at Journey House, Rich said she failed a drug test after using a CBD vape pen one night. As a consequence, Tillem suspended her pay – which she thought would only last a few days. But two weeks passed, and there was still no paycheck. When she raised the issue to a staff member, he told her she hadn’t proven herself yet and mentioned she was still dating someone who didn’t meet Tillem’s approval. (We’ll get to that in another installment.) Rich left Journey House voluntarily not long after that.

In 2017, Courtney Hammond was a new resident with three weeks clean, fresh out of jail after an overdose when Tillem recruited her to work for him.

Putting her economics background to work, Hammond helped Tillem create a business plan for Journey House. “That was when he first started trying to buy a center, and he did not have a business plan in place, and his financials were in disarray,” she said. Hammond toured prospective sites for the new center, did an assortment of administrative work and kept records for Tillem’s contracting business, TPML.

Her compensation package for roughly 30 hours of work each week included bed fees and a small weekly cash allowance, which she recalls was around $100 – “not worth the work I was doing at all,” she said.

But later, Hammond found out that her mom had been paying Tillem for her bed fees the whole time.

So, Hammond confronted him. “And the way he rationalized it to me, he was like, ‘Well, you know, you’re really entitled, and your mom has done a lot for you. So, I wanted you to feel like you were earning a wage.’ And I was like, ‘Well, I did earn a wage. You should not have been getting money from my mom as well.’ It’s kind of like double-dipping a little bit.”

As of May 2024, the Journey House website stated the following:

- Under “Your Recovery House”: “Our staff members are highly trained to give counsel as well as the much-needed monitoring and coaching to help clients overcome their present predicament.”

- “Your loved one will never have direct access to medication — our staff will assist in this process.”

- “You can feel confident knowing that our caring staff supervises and monitors all trips to ensure client safety and support.”

Just like many other positions at Journey House, the “staff” members – who monitor the recovery homes, conduct drug tests, manage medications, and sometimes provide transportation – are actually other residents. Many of them are early in their own recovery.

Leah arrived at Journey House shortly after she received a liver transplant from VCU Health for alcohol-related liver disease. After roughly four to six weeks in her new recovery home, she found out at a house meeting that she became the new assistant house manager.

Leah never asked to be in a leadership position, but she went with it – thinking it would be a good thing.

For nearly the next two years, Leah worked for Journey House without pay – she was assistant house manager, house manager (without an assistant), intake coordinator, driver. Not only was she not getting paid, but she wasn’t properly reimbursed for gas or mileage either. Leah spent almost $800 in gas and estimates Tillem reimbursed her $200 in total. She had to “throw a fit” just to get that, she said.

Journey House didn’t offer a place of healing and growth for Leah. As she poured herself into the program through all her unpaid responsibilities, it was impossible to focus on her own mental health, she said.

Leah told me her doctors advised her to leave Journey House long before she actually did because of the stress it caused. Finally, after almost two years of sacrificing her mental health for the organization: “I left that place worse mentally than I went in,” she said. “I don’t want other people to feel how I feel. And I don’t want other people to get ripped off.”

Another resident, who will be called Sophia, lived at Journey House at the same time Leah did.

I remember being enraged about feeling like they were using her so badly. … (It) just made me effing sick. … And she was really hurt. I mean, that’s a good example of how when you’re in this position of recovery, and when you’re vulnerable and whatever, something like that – that might not really have that much of an impact on you at other times in your life – can really throw you off. And it really did for her.

Sophia was also used by Journey House for free labor, she told me.

When I got to Journey (House), Mike Tillem was always very charismatic, and he would build people up in the sense that he made you feel special. Like, ‘Oh, well, because of your background, if you stay clean for this long, then you’ll be able to work for me.’ You know, making you think that you were coming into a situation that was going to be much bigger than what it actually was. And being in such a desperate situation at the time and so desperately wanting to be able to work in a more professional setting, I totally fell for that with him. But I noticed quickly that he did that with everyone. And these things never came through or they would turn into volunteer opportunity-like situations, which then was just straight up, I don’t want to say exploitation, but kind of.

After living at Journey House for about two weeks, Sophia started transporting residents in her personal vehicle. Tillem never paid her for her time, she said. He didn’t reimburse her for gas, either, even though he told her that he would. On top of driving, she helped with various tasks at the Journey House center, as many participants did.

Sophia worked an outside job to pay her rent at Journey House. After paying her basic expenses and driving participants for the Journey House program, she had no money left at the end of each week, she said.

I remember being so frustrated when being asked to do transportation, because I didn’t want to say no, because that’s just how I was. I wanted to be helpful and I wanted to be able to do more. And I felt like if I said no, then I was going to be passed up for opportunities that I really was hoping (for). Even though those opportunities didn’t actually exist, I was told they existed. So I always wanted to make sure that I could do as much for them as I could and be on their good side. …

It’s so strange because when you’re there and when you’re in it, it doesn’t seem like there’s this intentional stuff going on. But then you start hearing about things. And then it’s like red flags are going off, but you’re not really sure why. And then it’s like, especially now that I’m removed from it, it’s like, ‘Oh my gosh!’ You know what I mean?… I still don’t know how I feel about how intentional some of this stuff is, like Mike exploiting the participants for free labor. I know that he means well, but at the same time, I really don’t even know anymore because I’m one of those people that tends to believe that everybody’s good. And I will allow myself to get screwed over by everybody.

Families, government agencies and VARR collectively pay Journey House hundreds of thousands of dollars in program fees each year that are supposed to cover the cost of transportation.

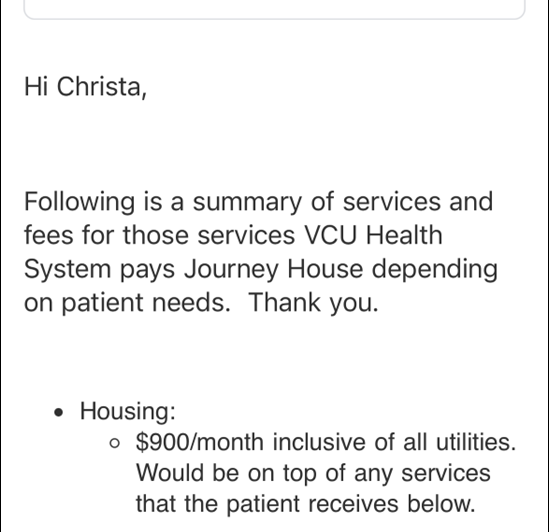

Here’s a summary provided by VCU Health, which has been paying Journey House to provide housing and aftercare for liver transplant patients since April 2020.

One of the residents Sophia drove to medical appointments was a VCU liver transplant patient, whose stay at Journey House was paid for by VCU.

Former residents also reported that house managers and assistant house managers got little to no compensation for their work.

Maria Williams, who reported an otherwise good experience at Journey House, told me she only got a $50 reduction of her weekly rent for being a house manager. Like many others, she did not believe that was fair compensation for the highly demanding role.

One former resident who lived at Journey House for about two months in 2019 told me his house manager “probably had over a year” of sustained sobriety. He was “definitely older and wiser and more mature,” the former resident said.

But many residents and employees who lived and worked at Journey House between 2019 and 2024 told me residents were sometimes promoted to a house manager position with barely one month clean.

A Journey House policy obtained in 2022 supports their claims. According to that policy, a resident can be promoted to house manager after just 30 days in the organization’s “intensive monitoring program.”

According to a former resident and a former employee who left Journey House within the last year, some residents were promoted to house manager with as little as two weeks of sobriety.

From the time the Journey House website was first archived in 2020 until May 2024, it claimed: “Each of our staff members are consistently active in the recovery community and have a proven track record of success.” (emphasis added)

After I sent the Tillems a list of questions for this article, the website language changed: “Each of our team members are consistently active in the recovery community and has a dedicated mindset to giving back to the recovery community.” (emphasis added)

Hammond spent time in several Richmond-area recovery homes before 2022. She recalled residents were often promoted to house manager with just 60 days clean. Even that, she said, “is just insane to me.”

Hammond elaborated:

Sixty days isn’t a significant amount of time, no matter what (recovery) pathway you take, to have done some really important introspective work and to give your brain and your body that reset, right? It doesn’t matter if you’re doing 12-step or SMART recovery or even Refuge Recovery, 60 days is really the beginning. And you’re barely out of withdrawals at that point in time. Your body hasn’t returned to normal sleeping patterns. So you haven’t developed any coping skills for cravings. … You can’t implement any structure if you don’t have any structure yet. You know what I mean? Like, how are you supposed to manage other people when you’re still learning how to manage (yourself)?

Former resident MJ believes high turnover is partly to blame for having house managers in early recovery. While living at Journey House for roughly half of 2023, “I saw a lot of people coming and going,” she said. Journey House staff were “kind of, at one point, asking everybody” to be a house manager.

Hammond made a similar comment about turnover:

“I’ve been in recovery in so many different states and cities, and I’ve just never seen anything like what goes on in Richmond,” she said. “You have a lot of turnover, you have a lot of craziness going on in the houses. And I just found while I was out (in California), it was a much more stable environment.”

>Dropdown page navigation menu<

- The business of recovery: a fast track to success

- ‘We can help you’

- The Medicaid cash cow at Journey House

- ‘The guys at the top are greedy’

- When clients are ‘staff’

- A whole house fell through the cracks

- Medication ‘monitoring’

- Playing doctor

- Urine drug testing: false claims

- Silence all the way to the top

- A note on solutions

A whole house fell through the cracks

In mid-2023, Hannah walked up to her new Journey House recovery home with three days sober. She was still detoxing, sweating, hating herself after yet another alcohol binge, but desperately wanting to turn her life around. Her dad wanted that for her too, she said, so he wrote a check for her first 30 days in the Journey House program.

(Hannah gave me permission to use her real name, but I chose not to so I can relay the details in her story without compromising the identity of her housemates. Their names have all been changed.)

Hannah lugged her three suitcases through the front door, looked around, and realized no one else was home. For what felt like the next two hours, she sat in the house by herself. “And then a girl named (Tracey) busted in the door,” she said. After a brief introduction, “(Tracey) was like, ‘I’ll show you where you should stay.’ And she said, ‘Wait, I need to go through your stuff. … Never mind. You don’t have anything. … Just tell them I did a thorough search.'”

Tracey showed Hannah to her quarters – an upstairs bedroom with three twin beds. “If I was you, I would take the bed all the way over here by the window,” Tracey told her, “because then you won’t hear the people throwing up in your bathroom.”

Hannah stripped all three beds of what looked like used sheets and cleaned the room as best she could, hoping to get company before the sun went down. But no one else showed up. “I laid down for my first night at Journey House, which was by myself, in the dark,” she said. “I didn’t sleep.”

A few days later, Hannah walked in the door to find a new resident, who will be called Rachel, sitting in the living room alone with her suitcases. “And I’m like, fuck. They’ve done it again. I can’t believe this shit. They just drop people off. And they’re like, ‘Abide by the rules.’ But nobody searches their shit.” (Two other sources confirmed it’s not uncommon for new residents to slip by without anyone searching their belongings.)

As no one was there to tell Rachel where to sleep, Hannah offered her one of the extra beds in her room. After Hannah went to bed, Rachel “stayed up the entire night tweaking,” she said. “She went through every inch of her stuff the whole night.”

Not long after that, Hannah started missing doses of her psychiatric medications, which caused her to get “the shakes,” she said. Per Journey House policy, the medications were held under lock and key by the house manager, who sometimes came home late or stayed out all night.

One weekend in early September, Hannah had two new housemates. The house managers were gone along with other residents who had overnight privileges, she said. One of the housemates who stayed behind brought home an edible psychedelic in the form of a mushroom candy bar.

“(The house leaders) are out doing drugs and getting drunk, and we’re like, ‘Fuck them. We’re going to do mushrooms,'” she said. “And it made me feel great. … For a couple hours, we walk down the road because we have no supervision. You know what I mean? It’s laughable. … I could have bought alcohol anytime I wanted, but I didn’t because I was there to get sober.” (From Hannah’s perspective, the psychedelic wasn’t harmful to her recovery. A relapse on alcohol would have been detrimental.)

After that is when “it starts to get wild,” she said.

(Another housemate) was like, ‘I have some acid at home. I’ll get my fiancé to bring it over.’ So I’m like, ‘Y’all do what you want. I don’t care.’ … I’m an alcoholic. I don’t know about the whole plethora of drugs. I’m thinking acid is a way to cope, like a mushroom candy bar. … So these (three housemates) stay up all night doing acid. My sober friend downstairs…says ‘(Hannah), why don’t you come downstairs and sleep in my room tonight? … Come down here and stay safe.’ … So I go down there and I sleep. When I wake up in the morning, they’re still on acid.

From there, things got worse.

The house manager is drunk all the time. (Another housemate), who takes over for her, I don’t know what her drug of choice is…is picking her face out, staying in her room. …

Next couple of nights, (two housemates) are fucking each other in my bedroom…smoking meth in my closet, doing fentanyl in my bathroom. … And I’m like, OK, I’m in a trouble spot. I’ve never seen these type of drugs before, but I know they’re dangerous. I know fentanyl is dangerous. … I have two oldies downstairs that aren’t saying anything, and I’m questioning it. Why aren’t they saying anything? Is the staff involved? How could the staff not be involved?

When Hannah couldn’t take it anymore, she went and “talked shit” to a staff member she believed was purposefully turning a blind eye to drug use in the home. (I spoke with that employee, who didn’t deny being confronted but said he would never turn a blind eye to residents using.)

Two more days went by. Then:

I was downstairs eating oatmeal, and I had a group text message that had a roll call of the (women who were being kicked out). … They could have beat my ass to death. I had to play dumb. Real dumb. …

So after I narc’d on everybody because I just couldn’t deal with it, (Rachel) came into my bedroom and said, ‘If I wanted to I could.’ (She) got the rest of her shit, stared at me and left. I had a taser thing under my bedroom covers and I’ve never been so afraid in my life.

Text messages I reviewed between Hannah and Rachel confirmed that Hannah reported nefarious activity in the house to a staff member and that Rachel was angry with her for doing so.

The former employee who denied turning a blind eye said that staff had been getting reports of drug use in the home for some weeks but that the residents had been passing their drug tests.

***

As is the case in many recovery homes, drug testing at Journey House was conducted by the house managers. They watched their housemates urinate in a cup and held onto that cup until they could turn it over to Adams, or whoever the specimen collector was at the time. This left ample opportunity for house managers and others to tamper with the samples – swapping out someone else’s clean urine for themselves or a friend, for example.

“The fact that (house managers) do these drug tests, and then use these drug tests to then report to the court that can then land somebody back in jail or losing their child or whatever it is, it makes me sick,” Sophia said. Urine samples were often left sitting around for days, she said. “They could have been tampered with by anybody in the house.”

Before Adams took over the specimen collector position in 2023, that position was filled by a Journey House resident. When Sophia lived at Journey House, the resident who worked for the lab left samples sitting at the center for days, she said.

There was just no checks and balances. And so regardless if someone seems like they could possibly tamper with things or not, the fact of the matter is, in a professional setting, you have to have things set up so that they will not be tampered with. That option shouldn’t even exist. So whether or not they were tampered with, I don’t know. I really don’t know. But it’s just the fact that that’s even a possibility is just crazy to me.

When Adams started working at the Journey House center in March 2023, he said the office he moved into was “worse than a kitty litter box.” There were urine samples “laying on the counter everywhere,” some older than 30 days. In one cabinet, he found samples dating back to October 2022.

***

The former employee Hannah confronted told me that eventually, someone outside the organization came forward with proof of drug use in the home, and then the residents started admitting to it. Seven women in that house relapsed, he said.

Adams confirmed that the house manager and two of the residents in Hannah’s home had been using before Hannah even arrived. “They kept having problems with the residents being able to get drugs and using in the house all the time,” he said. “But it just seemed like Mike (Tillem) didn’t care or bother to do anything about it.”

At one point, Adams said, Tillem told him to stop reporting issues to him.

He got tired of me coming to him. And he told me to start talking to (the Journey House operations supervisor) about it. He said everything goes to (her) that I have issues with. … I knew what Mike was doing. He wanted to make sure he’s clean of any wrongdoing. He’d rather have me tell someone else so he’s not catching shit later.

After Hannah’s housemate threatened her, she didn’t feel safe there anymore, especially because the back door didn’t lock, she said. Hannah told me she reported it to the staff, but no one ever fixed it. (Two other sources also reported issues with main doors not locking at Journey House recovery homes.)

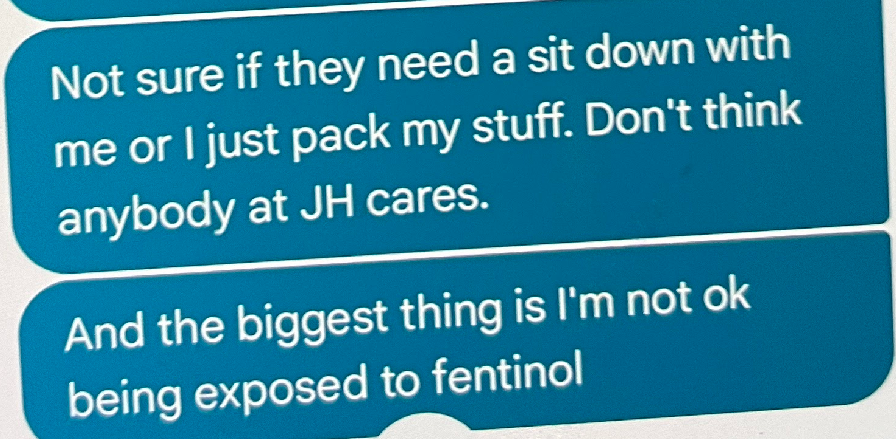

On Sept. 11, when a house manager asked her why she was planning to leave Journey House, Hannah cited some family issues and then wrote:

Not long after that, Hannah’s husband picked her up.

“The only reason I’m at my house is because my husband had mercy on me,” she said. “There’s people there that don’t have husbands or family.”

When Hannah first reached out to me in January, she wrote, “My sponsor wanted me to reach out to you. She passed away…after I left Journey House. This is for her and everyone stuck there.”

>Dropdown page navigation menu<

- The business of recovery: a fast track to success

- ‘We can help you’

- The Medicaid cash cow at Journey House

- ‘The guys at the top are greedy’

- When clients are ‘staff’

- A whole house fell through the cracks

- Medication ‘monitoring’

- Playing doctor

- Urine drug testing: false claims

- Silence all the way to the top

- A note on solutions

Medication ‘monitoring’

Hannah wasn’t the only resident to have medication issues.

Problems inevitably arise from putting residents in charge of other residents’ prescriptions, especially controlled substances.

Between late January 2021 and June 2022, Journey House submitted seven medication-related incident reports to VARR, two of which showed house leaders mismanaging – and potentially using – other residents’ prescription drugs.

March 22, 2021, Hawthorne House (summarized)

A resident’s urine screen showed she was positive for benzodiazepines – a controlled substance that was not prescribed to her – on 3/17 and 3/20. Staff discovered that the only resident in the house with a benzodiazepine prescription was missing six pills. When questioned, the resident with access to the medication provided inconsistent stories. The resident who came up short was able to get an extension of her medications – her psychiatrist “was advised that the assistant house manager mismanaged her prescription.”

Dec. 9, 2021, Lakeside House

- “(Redacted) admitted to staff before a drug screen that he has been taking Suboxone not prescribed to him. After further discussions, he admitted to offering to buy Suboxone from his housemates. He said that he has been buying various strips from them for 2 weeks.”

- “(Redacted) attempted to get a Suboxone prescription from Dr. Breslin, but was placed on Gabapentin instead, that he did not take. He continued to offer to pay for others’ Suboxone.”

- “New house leadership is in place. Suboxone has to be monitored at all times during administration…”

- “Mandatory house leadership meeting 12/12/21 with specific emphasis on Suboxone administration.”

(Medication-related incident reports Journey House submitted to VARR between Jan. 28, 2021 and June 25, 2022 are available here. I was unable to access incident reports submitted outside of that time frame.)

While residents were strictly prohibited from mismanaging medications, this practice was allegedly condoned at higher levels of Journey House management.

>Dropdown page navigation menu<

- The business of recovery: a fast track to success

- ‘We can help you’

- The Medicaid cash cow at Journey House

- ‘The guys at the top are greedy’

- When clients are ‘staff’

- A whole house fell through the cracks

- Medication ‘monitoring’

- Playing doctor

- Urine drug testing: false claims

- Silence all the way to the top

- A note on solutions

Playing Doctor

When residents exited Journey House, they often left their prescriptions behind. Instead of properly disposing of those medications, staff have been holding and occasionally re-distributing them to new residents, Rob Adams said.

He first learned about this practice directly from Michael Tillem.

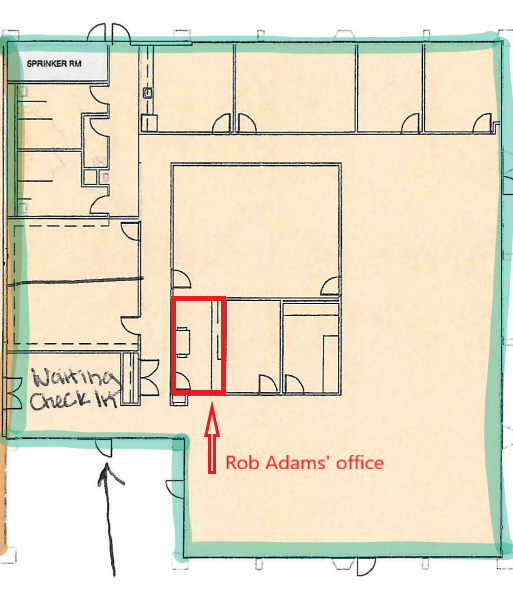

One day, when a house leader brought urine samples to Adams’ office, he also handed Adams some prescription bottles that were left over from participants who exited Journey House. Adams planned to ask a staff member, who will be called Audrey, what to do with them.

So, before I can even get to that, Mike poked his head in the door and he says, ‘Hey, those meds, set them on that cart.’ And he said, ‘Rob, I’ll be right back.’

When Tillem returned:

He was like, ‘Yeah, we’re going to need to keep this. … Don’t ever throw away Suboxone or buprenorphine.’ … And he said, ‘But hang on to these until (Audrey) gets back because we keep these. So if another participant needs it, we’re able to give it to them.’

After that, Adams started to see this practice unfold. He recalled a resident who came to Journey House with 30 days clean. Her initial drug test that day was negative for any controlled substances, but a couple days later, she tested positive for buprenorphine – the synthetic opioid found in Suboxone. When Adams reported the positive result to Audrey, she told Adams that she gave the new resident some Suboxone to hold her over until she could see a doctor.

“You could literally walk into (Audrey’s) office right now,” Adams said in an August 2023 interview, “and I know where she keeps (the medications) because Mike had me take the meds from my office to hers.”

And to condense it all, she literally sat there at her desk and filtered whatever was there. … So she had like three bottles of Suboxone for three different patients. … These participants are long gone. … So what she did is she took one bottle of Suboxone, opened it and then took all the other Suboxone and dumped it all in one. … And some stuff that she said, ‘I don’t really need this or I don’t need that.’ Now there are some of those drugs that they have that I honestly don’t know what it is.

A house manager who lived at Journey House the year before Adams arrived confirmed that Journey House staff stockpiled the medications residents left behind. “They would talk about how much Suboxone they had in particular,” she said. “(They) kept it in their desks.”

On one occasion, the house manager overheard staff talking about giving a former resident’s Suboxone to a new resident who was “detoxing really bad.” She didn’t see whether they followed through with it.

A former resident who left Journey House in 2023 told me she was struggling with anxiety and went to Audrey for help, thinking Audrey would connect her with a physician. Instead, Audrey gave her 15 Hydroxyzine pills from someone else’s prescription bottle and told her to come back if she needed more. “I just trusted (Audrey) because she was running the place,” the resident said.

Adams told me about another resident who came to Journey House straight from jail with a history of heart problems and high blood pressure. The resident told Adams he didn’t get his blood pressure medication from the jail, so Adams sent him to Audrey to schedule a doctor’s appointment.

Adams, a former Emergency Medical Technician, was later shocked when the new resident said Audrey gave him blood pressure medicine she had on hand.

“I couldn’t believe it,” Adams said. “Here’s the problem. Depending on your level of high blood pressure, you could kill someone giving them too much. … How does she know what he needs?”

Adams felt compelled to speak up.

I said (to Tillem), ‘That’s a little worrisome. You just got to keep an eye on this guy because whatever y’all are giving him, it could be too much.’ I was like, ‘It could make his blood pressure go down too low if you’re giving him too much.’ … And then his comment was, ‘Ah, (Audrey’s) been doing this long enough. She knows what she’s doing.’

Former employees say Tillem wasn’t always clear about his program’s limitations when presenting it to families who brought their loved ones to Journey House for help.

“He was selling something that wasn’t actually what it was,” Brittany Rich said. He made Journey House sound like “an actual rehab.”

Adams said the same thing. His office sat between the front entrance and day room, so he was well positioned to hear Tillem’s conversations with visitors.

On many occasions throughout the five months he worked there in 2023, Adams listened to Tillem describe the Journey House program with treatment-esque language.

Sometimes Tillem showcased Adams, who came to work in scrubs, as if he were a currently credentialed medical professional there to assist with their loved ones’ healthcare needs. “He would even tell family members that I would keep check on vitals, etc., of any participant in detox,” Adams said. “He would say I’m the lab technician, I collected drug screens, and I’m also a medic and if there was any health concerns or issues with their rehab, I would be the one to address it to 911…” (Adams’ EMT certification expired in 2016.)

Community members appear to have also been confused about what Journey House was qualified to provide.

The 2019 article recognizing Tillem as an “Allen & Allen Hometown Hero” claimed that Journey House offered counseling and healthcare services and that Tillem had “run recovery and detox support services…for over 10 years.”

In a 2021 blog post on “local charities that make a difference,” Allen & Allen attorney Christopher Toepp wrote: “Journey House founder Michael Tillem provides an array of resources, from housing to transportation services, not to mention counseling and health care support.”

In June 2021, Tillem found himself before the VARR Standards and Ethics Committee after Journey House was caught presenting a participant “treatment plan” to Henrico County – something no one at Journey House was qualified to provide.

The three-page document even listed recommended medications:

—–

In response to a questionnaire from VARR, Tillem revealed that the treatment plan was created by the same employee (a non-clinician) who was promoted from participant to care coordinator within weeks of getting clean less than two years earlier.

Per that questionnaire, Tillem also stated that was the first and only treatment plan Journey House had created.

In discussions around preparing a letter of reprimand to Journey House, VARR committee member Dorothy Tompkins wrote:

(T)here could be a statement that it is of significant concern that The Journey House actions and activities have been referred to this committee on several occasion(s)…

The committee decided to recommend a six-month suspension of Journey House membership to the VARR board, but it appears the organization’s membership was unaffected. (At the time, two of Tillem’s business partners were on the VARR board – David Rook and Jimmy Christmas.)

The issue wasn’t discussed during the open portion of the next VARR board meeting. But VARR expenditure reports showed Journey House experienced no interruption in funding. In monthly payments over the next fiscal year, the Tillems received more than $350,000 from VARR – money that was designated for VARR-certified operators only.

The treatment plan and associated correspondence between VARR committee members are available here. (All documents were obtained through a FOIA request to Chesterfield County, where then-VARR board member April Hutchison worked and received VARR-related emails.)

The Journey House website displays a one-sentence disclaimer that the organization is not a treatment facility. But several other places on the website, as of May 2024, indicated the opposite. For example, about halfway down the homepage:

When asked about this language, Tillem responded, “As you can see on our front page, we clearly state that we are not a treatment center. I want to thank you for letting us know about the treatment language deep in the website. We have fixed this issue.”

They did fix the issue, for the most part. Five areas on the website were revamped to remove statements claiming or implying that Journey House provided treatment, counseling and healthcare services.

Side by side comparisons of the website changes made after I raised questions about misleading advertising can be viewed here.

>Dropdown page navigation menu<

- The business of recovery: a fast track to success

- ‘We can help you’

- The Medicaid cash cow at Journey House

- ‘The guys at the top are greedy’

- When clients are ‘staff’

- A whole house fell through the cracks

- Medication ‘monitoring’

- Playing doctor

- Urine drug testing: false claims

- Silence all the way to the top

- A note on solutions

Urine Drug Testing: False Claims

As the former specimen collector for Diax and then Ethos Laboratories, Rob Adams was stationed at the Journey House center due to the high volume of urine samples Journey House sent to those labs for testing – almost as if Journey House were a medical treatment facility.

It’s normal for recovery homes to conduct routine and random instant drug tests to promote accountability for residents’ sobriety. It’s also normal for them to send a urine sample to a certified lab for confirmation testing if the sample is positive for illicit or unprescribed substances and if the resident does not agree with the instant test results. Even a 2020 version of Journey House’s drug testing policy states, “If you test positive for drugs without having used any substances, the specimen will be sent to the lab for confirmation.” (emphasis added)

Government healthcare programs, such as Medicaid, only pay for lab testing when it’s medically necessary. That means the tests are ordered by a treating physician based on each patient’s unique needs, and the results are used to guide medical decision making.

It is not normal or considered “medically necessary” to send routine standing orders for lab confirmation testing multiple times per week for every resident in a recovery house – many of whom are also tested by community corrections, drug courts and outpatient programs. Nor is it medically necessary to order lab tests for “patients” who have no connection to the ordering physician.

But that’s exactly what’s been happening at Journey House.

According to Adams and former residents, Journey House collected two samples per week from every program participant and automatically sent all those samples to the lab, along with the residents’ Medicaid information. On top of that, residents and house managers were tested randomly with instant drug screens. Those samples were also sent to the lab, regardless of the results.

There was no physician at Journey House or any medical professional at all. But there was a physician’s signature automatically populated on every lab order.

Dr. Laura Toombs is a primary care physician, who is board-certified in family medicine and addiction medicine. She never saw Journey House residents and didn’t know anything about them, yet her electronic signature appeared on each order form, certifying the test was medically necessary for her “patient.”

Toombs confirmed she gave Tillem permission to use her signature:

From what I understand, I’m just sort of a figurehead in terms of them being able to order labs, but the labs are ordered and processed by a nurse practitioner and other staffing on site, and that standard operating procedures are in common sense, are used where they have their routine urine specimen testing, which they do periodically just to help hold residents accountable in their recovery path. And I agreed to let them use my name so that they could actually send the specimens to a laboratory to be processed, that there was no other way for them to do it.

(After she talked with Tillem, Toombs told me she was mistaken about Journey House having a nurse practitioner.)

I told Toombs what former residents and employees reported to me – the high volume of samples automatically sent to the lab, including samples from instant tests that produced negative results.

She responded:

I just assumed when I engaged with them that they were going to proceed the way I had seen other recovery houses go about their daily operating business, like you describe. I don’t know to the effect of what their policy is or the volume (of tests) that they send. … I don’t want them to be fraudulent or wasteful in the management of resources. I just don’t know any more because I guess I just went on, you know, sort of a perception of good faith that they were going to be, I don’t know, reasonable. … I felt like it was a way (for me) to serve the recovery community. I don’t get, you know, compensated or anything.

Absence of medical necessity wasn’t the only issue with Journey House drug testing practices.

The samples were collected by house managers – other residents – who often didn’t seal, label or transfer them properly. By the time residents brought samples to Adams for processing, they were sometimes days or weeks old, piled in Walmart bags, “spilling everywhere,” he said. (Residents who lived at Journey House before Adams started there told me the same thing.)

Leaking samples could have been contaminated, Adams said, so he discarded those along with any old samples he sometimes received for residents who no longer lived there.

That was a problem for Journey House and Misty Roberts – the lab sales representative who secured Journey House’s partnership with Diax and then Ethos (when Diax closed).

After Journey House notified Roberts that Adams discarded some samples, Roberts gave him clear instructions to process every sample Journey House told him to process, no matter what. “So whatever cups they wanted me to send, I sent,” Adams said.

Here’s what Roberts told me:

The only time that I contacted him about throwing specimens away…is because he would decide if somebody didn’t do this or didn’t do that the way that he liked it, then he would throw the specimens in the trash can. … The specimens were brought to him to literally put into a computer system. That’s it. And if you don’t like the way they bring them in, or the bag is this, or the urine leaked a little bit, whatever, there was always an issue. It’s not up to you to trash somebody else’s specimen. You have to go to the facility or the physician and say, ‘What would you like me to do with this?’

I asked Roberts how that was supposed to work with no physician on site:

The doctor who was on all the forms, (Adams) never saw her, never met her. … And so how would he even be able to run something by her if a sample was being brought to him that he thought shouldn’t be sent in (to the lab) because it was leaking, possibly contaminated, or from a resident that wasn’t there anymore?

It’s not contaminated. They’re in individual bags with security tags on them. …

He told me that residents, house managers, would be bringing in these cups and sometimes they would be leaking. And so then the sample could be contaminated with someone else’s urine. And then also when it comes to the —

They’re in their own cups. They can’t be contaminated. What, are the cups jumping into each other? It’s impossible. They’re in individual cups and individual bags.

But they weren’t in individual bags, is what I’m saying. He said that they were brought to him and they were leaking everywhere.

No, they weren’t.

How do you know that?

Either way, it’s not up to (him). He works for the lab. It’s not up to him to decide anything about any patient’s specimen. Not one iota of it. …

(As the Ethos collector, Adams had to certify that every specimen had been “collected, labeled, and sealed in accordance with applicable regulatory requirements.” Ethos didn’t respond when asked what those requirements were.)

So what about for residents that aren’t there anymore? I know you’re saying that it’s just his job to put them into the computer and send them. But does he have no ethical —

Think about the logic behind that. You can’t collect a specimen from somebody that’s no longer at the facility.

Right. But I’ve had plenty —

So what is he trying to say? That they collected specimens from people that didn’t really exist? That doesn’t even make sense.

No. What he’s saying is that, and which other residents have told me also —

There’s been no specimens of patients that aren’t there any longer. We wouldn’t have their specimen if they weren’t there.

So what he and other people have also told me is that sometimes the house managers will collect the specimens, but then they sit around for days, and so by the time they actually get to Rob (Adams), they (the residents who produced the urine samples) might be gone. And so, let’s just say that happened. Does he not have any ethical responsibility at all to say, ‘Hey, this person’s not even here anymore. I shouldn’t be sending this to the lab.’?

No! That’s the issue with him and doing his job, is that’s not his job to decide.

OK.

He cannot make any decisions at all. The only thing he can do is to put the patient’s information in the computer, which nine times out of 10 is already in the computer. Hit the button and save it and send it to the lab.

According to Adams, there is at least one thing Tillem got in exchange for sending hundreds of samples to these labs each month: Another (functional) Journey House staff member paid for by the labs.

Adams processed close to 500 samples per month, he told me – sometimes a little more. That was apparently enough to justify having him stationed at Journey House, but processing those samples wasn’t a full-time job. Every day, Adams finished his work for the lab between 11:00am and 11:30am, he said. For the rest of the day, he was on-call for Tillem – on Diax and then Ethos time.

At Tillem’s direction, Adams helped search new residents’ belongings, set up for IOP, clean the for-profit Journey House Behavioral Health office, and prepare for the annual golf fundraiser, among other tasks. Tillem even had a Journey House email address created for Adams, which I confirmed by reviewing some of the emails he saved. (Ethos also approved this, he said.)

Under both labs, Journey House created an ID badge for Adams with the Journey House logo and a made-up job title: Drug Screen Analyst.

As a former EMT, Adams was the only person at the center with prior medical training.

Tillem had him watch over new residents who were detoxing, monitor blood sugar levels for diabetic residents, and apply bandages and glue stitches for residents and a staff member. He was even asked to treat a new resident’s sebaceous cyst, he said.

Above photos show medical supplies Adams kept in his office at Journey House.

Adams was all-in at Journey House. He enjoyed being part of the team and finding new ways to contribute.

One day, after a resident overdosed in one of the recovery homes, Adams was talking with the house leader who administered Narcan the day before. She was venting about being the only one in the house who knew what to do in that situation.

“So, it got me to thinking,” Adams said. “I’ve pushed more Narcan than I ever want to admit to begin with. So, I said, you know what? I’ll get Narcan certified to where I can be a certified instructor and I’ll teach Narcan training.”

He brought the idea to Tillem and Kaeler McCollough, Tillem’s stepdaughter and Journey House’s director of marketing & communications. They loved the idea, Adams said. They told him how to become a certified trainer through the state’s REVIVE! program, which he completed in mid-July. Tillem and McCollough were involved every step of the way, Adams said. And he gave them every piece of paperwork associated with the process.

But when Ethos learned that Adams was going to provide Narcan training for Journey House staff and residents, his supervisors put a stop to it. Here’s how he remembers the conversation with them:

Ethos says, ‘Yeah, you can’t do that.’ … She said, ‘Basically, it’s laws against referrals and kickbacks.’ … She said, ‘It’s the process in which Journey House is trying to get you to do this.’ She said, ‘They’re using you because you’re an asset there. You are not working for Journey House. You work for Ethos.’ … So she tells me I can’t do it. And I was like, ‘OK.’

Adams relayed the message to Tillem, and he said Ethos told Tillem the same thing.

Not long after that, Adams got a call from Ethos stating he was no longer a good fit. In a subsequent phone call, he learned someone at Journey House told Ethos he went behind their back to get Narcan under the Journey House name.

Roberts told me the same version that Journey House allegedly reported to Ethos. She said that Adams, all on his own, “fraudulently represented himself as a Journey House employee…to the government…” Tillem didn’t know anything about it until Journey House was contacted by the Virginia Department of Health (VDH), she claimed.

Ethos did not respond to a request for comment, and I was unable to reach the founder of Diax, which closed in 2023.

Toward the end of Adams’ employment with Journey House, he had been raising a number of questions and concerns about ethical issues, he said – including the distribution of unprescribed medications to new residents.

Adams doesn’t know for sure why Journey House set out to have him removed, but he believes it was because he was learning too much and asking too many questions about what was going on there.

A few days after I emailed the Tillems a list of questions for this article on May 13, Adams told me he received a phone call from a blocked number. The man on the other end, whose voice sounded familiar, told him it would not be in his best interest to say anything about Journey House or Tillem. “If you do, it’s not going to end well,” the man said. “You’re fucking with the wrong people.”

Today, Michael Tillem holds a prestigious position on the board of the Opioid Abatement Authority – the state agency overseeing the distribution of more than half a billion dollars in opioid settlement money. He was appointed by Youngkin in November 2022.

>Dropdown page navigation menu<